Variance of Behavior Patterns

Towards Ritual Circumcision

by Rabbi Daniel Schur

June 1971

Ashland Theological Seminary

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the Degree of Master of Divinity

Major Pastoral Psychology and Counselling

Thesis Advisor: Dr. Irving Rosen

Abstract

Although ritual circumcision is extensively practiced by all factions of Judaism, I feel that the commitment behind their behavior is not a religious derivative. I am assuing that there is little or no religious commitment, but rather medical, in the Reform, Conservative, and Unaffiliated Jews. However, the Orthodox, submit their children to the rite of circumcision because of their faith in the tenets of Judaism. Their child's circumcision represents the covenant between themselves and their Creator.

Hence, my curiosity was aroused to find any factors, unique or interrelated, which could cause significant changes of behavior among the factions of Judaism. How, why, and how instrumental and influential are these factors within each faction's religious scope and definition of Jewish fulfillment?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTIONCHAPTER I: BIBLICAL DEFINITION AND BACKGROUND OF RITUAL CIRCUMCISION

CHAPTER II: ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF THE RESPONSES TO THE QUESTIONNAIRE

INTRODUCTION

To answer these crucial issues I compiled a questionnaire and mailed them to approximately 200 individuals, selected at random from my appointment book for over a period of the years 1968, 1969, 1970, in the Greater Cleveland area, including Warrensville Heights, Mayfield Heights, Shaker Heights, Cleveland Heights, University Heights and some of Cleveland proper. Seventy-five per cent of those sent out returned with all 67 questions answered.

After defining the necessary terms used, I will list and evaluate the responses, explaining them in relation to my own experiences, pinpointing incongruities, and then draw conclusions which will hopefully encourage constructive action to educate.

CHAPTER I

BIBLICAL DEFINITION AND BACKGROUND

OF RITUAL CIRCUMCISION

The rite of circumcision is defined as a Brith or Covenant. This usage is based on the verse in Genesis[1] where circumcision is the sign of the covenant G-d made with Abraham:

And G-d said unto Abraham: "and as for thee, thou shalt keep my covenant, thou and thy seed after thee throughout their generation. This is my covenant, which ye shall keep between me and you and thy seed after thee; every male among you shall be circumcised. And ye shall be circumcised among you, every male throughout your generation; he that is born in the house, or bought with money, any foreigner, that is not of thy seed. He that is born in thy house, and he that is bought with the money must needs be circumcised; and my covenant shall be in your flesh for an everlasting covenant. And the uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that soul shall be cut off from his people. He hath broken my covenant."Immediately after Abraham is commanded to circumcise himself, Abraham's name is changed from Abram to Abraham. Thus, the tradition of giving the baby his Hebrew name at the time of the circumcision[2]. It is at the time of fulfillment of the covenant, and because of the covenant that a child is given his name during the ceremony.

Careful examination of various passages throughout our biblical and talmudical sources, demonstrates the importance and status of the circumcision rite within Jewish practice.

Rabbi Ishmael says "Great is the precept of circumcision since thirteen covenants were made therein, the word covenant occurring 13 times in Genesis 17."[3] The Rabbi recognizing the importance of maintaining the rite of circumcision as a basic element in Judaism, had long before ordained that the rite of circumcision, observed properly and with certainty, sets aside the Sabbath observance.

Rabbi Jose concurred that "circumcision is a great precept for it overrides the strictness of the Sabbath."[4]

Rabbi Joshua Ben Karha says: "Great is the precept of circumcision for neglect of which Moses did not have his punishment suspended for even a single hour."[5]

Rabbi says "Great is circucision for despite all the religious duties which Abraham, our father, fulfilled, he was not considered 'tamim' (perfect) until he was circumcised."[6] As it is written in Genesis 17.1, "Walk before me and be thou perfect."

"Great is circumcision since but for that, the Holy One would not have created his world."[7] As it is written, "Thus said the Lord, 'But for My covenant by day and night I would not have set forth the ordinances of Heaven and earth'."[8]

Rabbi's teaching also relates that "Great is circumcision for it counterbalances all the other precepts of the Torah." As it is written in Exodus,[9] " ... For after the tenor of these words I have made a Covenant with thee and with Israel."[10] "The tenor of these words" refers to all G-d's precepts, "Covenant" is used synonymously with circumcision. Hence the balance between the precepts of the Torah with the covenant of circumcision.

Rabbi Eleazar of Modium said: "He who makes void the Covenant of Abraham our Father has no position in the World to Come."[11] Careful examination of Biblical sources[12] seems to indicate that the Rite of circumcision is a means, a sign, or symbol of the covenant. However, the circumcision, in itself is not defined as a covenant.

The Act of circumcision involving the removal of the prepuce does not fulfill the obligation of the Rite of circumcision. There are basic conditions to this rite or covenant[13].

The eighth day is a biblical prerequisite of the fulfillment of the Brith or covenant, and is stressed throughout the Jewish law. "And Abraham circumcised his son Isaac, at the age of eight days, as G-d had commanded him."[14]

As stated by Beth Joseph,[15] Ramah,[16] any circumcision that has been performed before the eighth day does not fulfill the original covenant of Brith Mila that G-d made with Abraham. Mere cutting or removing of skin, even according to Jewish law does not fulfill the covenant. Hence, if one circumcises a child prior to the eighth day, this individual has no share in the world to come.

Great is the importance of the fulfillment of the covenant connected with the circumcision, that if one who is circumcised has in mind to render himself by artificial devices uncircumcised, he has no share in the world to come.[17]We have thus far illustrated that Brith Milah is a sign or sumbol of the covenant, and that removing the skin of the prepuce is a means of fulfilling this covenant. However, this fulfillment is hinged on the concept of the eighth day which is biblical.

Another condition for fulfillment of the Brith Milah is that a stranger to Judaism, even if he is circumcised, or an Israelite who does not follow the rules of Brith Milah according to the dictates of the Torah, or one who is himself uncircumcised, or still, one who desecrates the Sabbath -- is forbidden to circumcise. Furthermore, if these individuals have circumcised,[18] we have made void the ritual of circumcision. For in order to fulfill the rite of circumcision, one must himself be imbued with a commitment and conviction of circumcision. Hence, it is not only the removal of the prepuce, but also the psychological, emotional, and religious state of the Mohel, the one who performs the circumcision, that allows the covenant to be meaningfully culminated.

Thus, in summary, ritual circumcision is based on ritual theology rather than on any medical or health doctrine. Removal of the prepuce does not ascribe meaningul fulfillment of the ritual Covenant of Brith Milah. Before the eighth day a Brith is declared void. An observant Jew must be the Mohel, the one who performs the circumcision; technically trained and religiously authorized.

Footnotes for Chapter 1:

[1]Genesis 17.9-14.[2]Genesis 17.5.

[3]Mishna-Nedarim 3-11.

[4]Nedarim 3-11.

[5]Nedarim 3-11.

[6]Nedarim 32-A.

[7]Nedarim 3-11.

[8]Jeremiah 33.25.

[9]34.27.

[10]Nedarim 32-A.

[11]Avoth 3-15.

[12]Genesis 17.9-14.

[13]Genesis 21.4.

[14]Genesis 17.

[15]Chapter 364, p. 196.

[16]Chapter 364, p. 83.

[17]The Mishna and Herbert Danby, 451-13.

[18]Ose Shalom, 364, small paragraph 5, and the Bach-Yera-Deya, 364.

CHAPTER II

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF THE

RESPONSES TO THE QUESTIONNAIRE

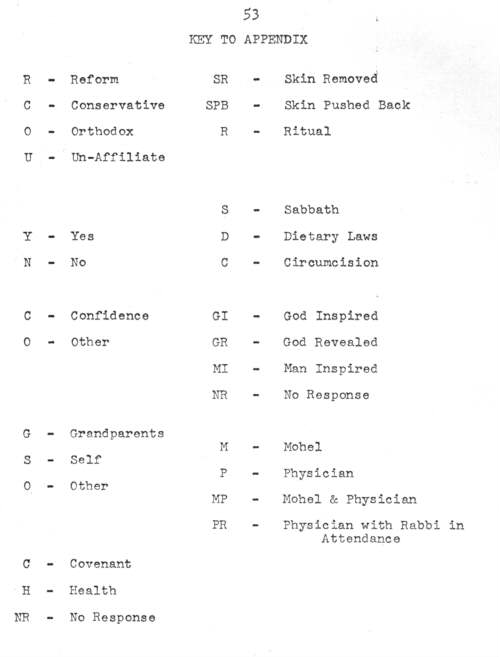

I am grouping, in this qualitative study, several related questions and answers in order to demonstrate and evaluate the similar or contradictory behavior patterns within or across the Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Unaffiliated. Thus, despite the given arrangement of questions, I can establish the manifested hierarchy of "religious" norms and mores intrinsic to the Jewish factions.

1. Do you belong to a synagogue?

Ans. This is the way I was able to ascertain the religious affiliation.

2&3. Are you intermarried; did this have an effect on your decision to have your son ritually circumcised?

Ans. Among the responses, there was little difference between the Orthodox, Conservative, Reformed, and Unaffiliated. The unaffiliated Jew did, though, show a slightly higher margin of intermarriage. The Orthodox showed none; yet, I am cognizant of some percentage of intermarriage even among this faction.

By definition, intermarriage refers to a situation in which one of the spouses has converted from a different faith into Judaism. Hence, among those who answered the questionnaire, about 50% of those intermarried felt obligated to accentuate their Jewish identity by entering their cuild into the faith, through a ritual circumcision.

4&16. What is your educational Hebrew background?

Ans. The responses indicated small difference between the Conservative and Reformed factions. Educational background of the Conservative and Reform parent ranges anywhere from one day Sunday School, to two day a week Hebrew School. However, a percentage of the Conservative also attend Temple Hebrew School four days a week. The limit of the Reform Hebrew school attendance was a Sunday School and two day a week sessions. The majority of the Orthodox attended Parochial School, Sunday School, four days weekly Synagogue Hebrew School, and afternoon day school. Curiously, the Unaffiliate's educational background ranged anywhere from no Hebrew school whatsoever, to a four day a week afternoon school.

5. Do you want your son to attend Hebrew School? Until Bar Mitzvah; until graduation; until the end of Hebrew High School?

Ans. All four factions seem to agree that they wanted their children to attend Hebrew School. Approximately eighty per cent of the Unaffiliated, Reform, and Conservative intend to have their child attend Hebrew School until their Bar mitzvah. As far as attendance until the end of Hebrew high school, a greater amount of Reformed parents, rather than the Conservative, anticipated this extended education. The only significant response to education until or beyond graduation, was evident among the Orthodox. About 90% of those who answered after graduation, added the word Yeshiva, suggesting the strong possibility of continuing their studies in a Yeshiva environment after graduating from Public High School. Also, among those questioned, some left the decision of Hebrew shcool duuration of education, up to the child's discretion.

6&17. Do you know the meaning of Brith Milah, circumcision?

Ans. No significant difference was noted between the four factions; all answered to the effect that they did know the meaning of the word Brith Milah, the Covenant of Circumcision. Yet, from my own experience, very few people encountered at a circumcision even knew the literal meaning of the word Brith Milah besides the significance of the word.

Among the Reform, Conservative, and Unaffiliatd, a significant majority felt that the reason and meaning behind circumcision was health. Their motivation, therefore, was not strictly religious, nor medical. It seems that their behavior is based on their belief that since circumcision is approved medically, they adhere to the ritual circumcision, providing they have confidence in the selected Mohel.

8&55. Did you choose the Mohel with confidence? Whom would you prefer to circumcise your son; Mohel, physician, Mohel with attending physician, or physician with attending Rabbi?

Ans. The response of all four factions of Judaism indicates that the Mohel was confidently chosen to compentently fulfill the ritual of circumcision. Yet there exists inconsistent feelings concerning competence, with religious and/or medical connotations. Medical competence, which involves removal of the prepuce, is a part of the ritual. Unfortunately, many call the Mohel to circumcise their child according to their reasons, for the purpose of health. They want a Mohel, yet, they have confidence in him as a common practitioner, but not really motivated primarily by his religious commitment and function. Therefore, the response to the alternatives of having a circumcision performed by a physician, Mohel with physician in attendance, or physician with Rabbi in attendance, incdicates a deviation of decisiveness between the Reform, Conservative, Orthodox and the Unaffiliated.

7&13&14. Who had the most influence regarding having your son ritually circumcised? Backround, self, grandparents, Rabbi, friends?

Ans. The feelings of all four factions were in consensus concerning the influence of their background motivating them to have a Brith. Their decision evidently seems to be based on emotions, unable to be articulated or explained.

Studying the tabulations shows a difference between the factions of Judaism. Of the Reform, 50% of the decision was made by the grandparents, and 50% made by the involved parents. What will happen to the rite of circumcision when this 50% passes on? In the Conservative group, 25% of the grandparents were the influential factor. What will happen when the 25% pass on? Of the Unaffiliated 45% stated that their grandparents influenced them. Again, what will occur when they pass on? Among the Orthodox, only 1% were influenced by grandparents.

Of the other responses as to the influential factors, the Orthodox listed the Halachah (i.e., the equivalent of G-d's law); religion; Torah law; and Biblical requirement.

The Unaffiliated were motivated by Tradition; cleanliness; health (bringing forth a new dimension: "I don't feel it was ritually necessary"); the proper naming of the child; telling the grown child "it was done the right way"; "we just wanted it done, though unnecessary"; ancient Hebrew tradition and health; family tradition; trust of the Mohel's qualification; gathering of the family to bring the male into the fold (carrying some implication of ritual); and finally, just one mentioned Jewish law.

The factors influencing the Reform include: tradition and heritage; "right thing to do"; viewing the ritual as an enhancement of Reform Judaism; Respect to parents; originally performed for health reasons, and can now be performed by an M.D.; for the future if the son wants to be a Rabbi; Jewish identity; hope that G-d will watch over the son (fear factor); Lack of introspective reasoning, merely a procedure which is automatically done; assuring the child of latitude to reach his own decisions as to religion.

The factors influencing the conservative are: "Ritual circumcision makes no difference" as long as it is for health; religion; Jewish construction; heritage and health; family meddling; naming and blessing the child; "Jewish peoplehood"; unnecessary but nice for Jewish tradition; Jewish law primarily, coupled with health benefits; "we are practicing Jews, and I hope my child will be too."

Hence, there is a crucial failure in the understanding of the need and meaning of true ritual circumcision. If its religious commitment is replaced by medical influence, then what is the future of the Brith Milah? If the majority of parents were aware of the controversy existing between the doctors themselves, how would this effect their attitudes now?

What is the controversy existing between Doctors?[1]

"Arguments against circumcision include the views that, like any other surgical operation, it is associated with certain infrequent but preventable hazards and complications, and that basically the procedure is unnecessary."

"Routine circumcision of the newborn is an unnecessary procedure. It provides questionable benefits and is associated with a small but definite incidence of complications and hazards. These risks are preventable if the operation is not performed unless truly medically indicated. Circumcision of the newborn is a procedure that should no longer be considered routine."

"Complications of circumcision may be realized as immediate or delayed. The immediate complications fall into three categories: hemorrhage, infection, and surgical trauma. Hemorrhage is the most common of these immediate complications. It may be caused by inadequate hemostasis, blood coagulapathies, or the existence of anomalous vessels. Patel studied 100 consecutive male infants who were circumcised at birth and who were re-evaluated six to eighteen months later. He found thirty-five instances of hemorrhage, or which four required sutures. Infections of the wounds in circumcision are also a fairly common complication. It is manifested by local inflammatory changes, ulceration and suppuration. Occasionally, infection may lead to more serious complications, such as partial necrosis of the penis, or it may be a source of septicemia."

Recurrent infection of a nonretractable foreskin in an older child seems a more legitimate reason for recommending operation to allow drainage. The fortunate rarity of this condition in infants is probably the result of the persisting attachment of the prepuce to the glands.

As to the argument that the circumcised penis is more aesthetic, one is reminded that beauty is in the eye of the beholder; and that most Renaissance works of art show the male organ draped, if not with a fig leaf, at least with a foreskin.

The argument is also put forth that the circumcised organ is more hygienic for the prepuce collects nasty secretions. So does the ear, but the removal of this rather ugly appendage is frowned upon, and in one famous instance cutting it off led to war -- the so-called-war of Captain Jenkins' ear. One man can be grateful that this worthy mariner did not lose his prepuce under similar circumstances, for it is likely the battle would still be raging.

It is interesting to note that all of the reasons advanced for routine circumcisions have continued with the prevention of certain conditions; not with the establishment of a condition, such as strong teeth and bones or a normal cardiac reserve. Dr. Robertson has stated: "Avoidance of harm is not to be equated with provision of benefit; just because it doesn't kill, that doesn't mean it helps."[2] Circumcision is rarely performed or requested on the basis of its medical indications. Doctors Shaw and Robertson interviewed eighty mothers of newborn male infants, and found that 72% denied that a physician had ever discussed circumcision with them. The reasons for or against circumcision stated by 106 physicians questioned, bore little if any resemblance to the reasons advanced by the 80 mothers. The results cast doubt on the belief that the decision to circumcise is reached in any scientific manner. Thus, again, how would the removal of the medical factor influence the religious aspect of the ritual circumcision?

In the JAMA issue of December 21, 1970, an article submitted by Lawrence D. Freedman, M.D. refutes the preceding excerpts from the September issue. He defends routine circumcision, as having saved innumerable young men countless hours of having to perform the constant tasks of retracing their foreskin and extracting their smegna.

In the same edition, Ronald S. Nadel feels that circumcision plays a prophylactic role in the prevention of disease.

Marvin C. Daley writes "adult circumcision is a more painful experience than newborn circumcisions and the hazards are greater."

To me as a Mohel and having practiced for over twenty years, both arguments, pro and con, seem very unimpressive and unconvincing. I fail to comprehend shattering effects of the arguments, considering the percentages that are left unquoted. Though the Mohel's skill in the art of circumcision is complementary to his religious functioning, the spiritual hand in hand with the physical, the medical articles seem to imply that the Mohel is more competent that the so-called medical giants. My colleagues and myself have never encountered all these complications illustrated by the physicians' articles. However, if some enlightened parents were to prove vulnerable to the opinions of skeptical doctors, the survival of ritual circumcision is precarious. The occurrence of such a situation has unfortunately earned a place in the Jewish Encyclopedia:

"After having for centuries been practiced as a distintive Jewish rite, circumcision appeared to many enlightened Jews of modern times to be no longer in keeping with the dictates of a religious truth intended for humanity at large; and its abolition was advocated, and made the shibboleth of the 'Friends of Reform' by 'Reform-freunde' in Frank-fort-on-the-Main in 1843."10,11. Do you name a baby boy at Circumcision or at Temple; did it make a difference to you where; is it because of the child's Hebrew name that you decided to have a ritual?

Ans. Questions 10-12, and 31 and 51 deal with the name of the child. Due to my personal disappointment in the responses which were contrary to experience, tabulation would just conceal reality. If I were to reiterate the average question directed to me before a circumcision, the question would revolve about the name. The giving of the name plays an important part in the motivation of having a ritual circumcision performed. If there is any ritual attached to the circumcision, it is the desire of the parents to give the child a Hebrew or Jewish name, perhaps after the name of a deceased relative. However, the responses to the involved questions, lacked emotional feeling toward the naming procedure for the child. Only the Orthodox answered the question as to whether the parents approved of their son having a Hebrew sounding name.

Concerning the connection between the child's Hebrew name and the performance of the ritual, again, an overwhelming majority of the factions denied the interdependence. Yet, again, experiencing various discussions and questioning with the parents prior to the circumcision, they focused their interest on the name. My twenty years experience gives me good reason to assert that despite the response to the questionnaire, many of the participants in the ritual circumcision had the circumcision mainly becuase of the name. Even in situations where the grandparents were instrumental in persuading their children to have a ritual circumcision, they exclaimed: "My grandchild will have a ritual circumcision because that is the only way he is going to get his name; otherwise I do not want him to perpetuate the name of his ancestors." Hence, the assumption that though the parents are not committed to a ritual, but rather to a medical significance, the little ritual present, is manifested in the name-giving ceremony.

20,22,23,26. What was your immediate reaction to your son's circumcision; did you regret having a ritual; were you worried

Ans. All seem to unanimously agree that they did not witness any regret or fear of having the ritual. Hence, it seems that the list of complications presented in the September JAMA are neither verifed nor supported by experience. Indeed, had any complications occurred, the parents would have readily responded against medical circumcision.

The Mohel, then, who functions as the religous instrument in the fulfillment of a Biblical commandment, is performing a medical function, and is trusted to have experienced proficiency, such that the remarks made by those opposing medical circumcision have little significant relevance.

27. Does the fact that your child was ritually circumcised make any difference to you?

Ans. 45% of the Reform, 33-1/3% of the Conservative, and 57% of the Unaffiliated replied that it was of no difference to them whether their child was ritually circumcised or not.

This response yields confusion and contradiction. If the parents were satisfied with the ritual Brith, then why do they remain apathetic to having their child ritually circumcised? This indicates that the ritual aspect of the Brith has been neglected by many. Their satisfaction and happiness was not in actuality aesthetic or spiritual. They viewed the circumcision as a medical prefernce, performed by a medically competent Mohel. They stressed the extrinsic value of the outcome of the circumcision, overlooking the intrinsic value of the ritual ceremony.

18. What do you think was done to your son? skin removed, skin pushed back, ritual?

Ans. Reviewing the tabulations, it is noted that 25 out of 106 parents, or approximately 25% (11 from the Reform, 9 from the Conservative, and 5 from the Unaffiliated), responded that they had no idea as to what was being done to their son.

47,50&59 Do you know the historical background of the Brith Milah? Did you know the meaning of Brith Milah before or after the circumcision; what Patriarch is connected with Brith?

Ans. Very few were aware that Abraham was the first to be circumcised, confirming the large percentage who did not know the meaning of historical background of the Brith (50% of the Reform, 70% of the Conservative, 100% of the Unaffiliated, and 0% of the Orthodox).

62. Do you feel having a homeland in Israel had any bearing on your decision for your son?

Ans. Although the State of Israel has motivated more pride in Jewish identity, and there definitely exists among today's youth a pride in Jewish identification, 98% of those questioned stated that Israel was not an influential factor at all. Apparently, there is a tendence to base Jewish identity on ritual circumcision, the basic covenant incumbent to a Jewish male.

However, such feelings misinterpret the awakening of Jewish identity, which should also stimulate immense interest in Jewish ritual. For what is identity without a spiritual identification? This phenomenon is directed to the attention of educators and spiritual guides. From lack of commitment they have avoided capitalization on this strong insurgence of Jewish identity. They have failed to teach our youth to incorporate Jewish ritual and behaviour with spiritual pride.

34. What is being religious?

Ans. As expected the responses differed between the four factions:

Reform definitions included: considering yourself so; living a moral life; fear and hope in G-d; having love in the home; ethical laws; following the Ten Commandments; identified, committed and a practicing Jew; lighting the Sabbath candles; being true to self and family; a way of life; a belief in the theory and philosophy of G-d; religion does not mean going to temple, but serving G-d as best you can; observing and conserving the tradition; observing the Sabbath, not dietary laws; a deep Jewish feeling; family unity and togetherness.

Conservative definitions include: what you think in your heart; not being a hypocrite; observing moral and ritual codes; bringing up chilren to be decent human beings; to follow some customs of our religion; following the Golden Rule; believing in our heritage; not eating pork; believing in G-d and in Judaism; doing the best one can; following the principles of the Torah excluding kosher diet and Sabbath observance; observance to the extent one wants to; having a set of beliefs and values within a certain group; do's and don't's; personal belief; believing in a supreme being; observing the tenets of the Jewish religion, Conservative branch (no dietary laws, no Sabbath observance); to feel a sense of Jewishness in things done; believing in G-d and thought; no labor or driving on Saturday; observing rituals; adhering to the precepts of our faith that are meaningful to us; helping the poor.

Orthodox responses include: adhering to the Torah; observing the mitzvoth; observing the Halachah, Jewish Law.

The definition of religion for the Unaffiliated include: feeling that G-d is ever present and influences decisions at all times; preserving religious tradition; being a good, honest person; being righteous on what you do; following the ideals of G-d; having a feeling for G-d; religion means following the concepts of Orthodox Judaism; firmly believing in something and ordering one's life accordingly; following the laws, traditions, customs and rituals of a certain given sect and believing sincerely in them; taking part of religious activities, excluding Sabbath observance and dietary laws; observing the traditional holidays; observing all the Orthodox laws; following Hebrew and tradition of Zionism; respecting G-d and his commandments; observing age old laws; following the Torah excluding observance of the Sabbath and dietary laws; attending the Temple; believing in something more powerful than themselves; hypocrisy.

53&54. Do you know what day the Brith Milah should be performed; are you in agreement with a pre-eighth day circumcision ceremony?

Ans. Overwhelmingly, the responses indicate that the day of the circumcision makes no difference to them, Conservative, Reform, and Unaffiliated parents. However, I thought that perhaps the parents did not really know when a circumcision must ritually be performed. Yet, they truly did not care about the eighth day, proving that the performance of the Birth Milah was guided by medical, not ritual, importance.

64&65. Do you belong to a Temple because of social reasons, living closer, or commitment to Temple idealogy? Do you enjoy or find meaning in the Temple services?

Ans. The majority of the three factions other than the Orthodox, claim to have found enjoyment and meaning in the Temple services. However, is it not strange that Temples are empty during services, despite the avowed commitment and meaningfulness of an idealogy or Temple service? Contrary to my assumption that very few parents are intellectually committed to Temple idealogy, the responses indicate a reluctance among the parents to admit that they were part of a social pattern in belonging to the Temple. It seems that the people were quite emphatic in justification of their idealogical commitment to the Temple.

Is the individual thoroughly aware of the tremendous inconsistency in the emptiness of Temples and the claiming of being committed to the Temple idealogy? Presumably, commitment to a Temple idealogy requires participation in Temple services. Jewish awareness is not enhanced by constructing a beautiful edifice and calling it a Temple. The beautiful ideal of a Jewish homeland will not nurture the basic principles and tenets of Judaism. To appreciate one's religion, one must fully be a practicing Jew in all aspects of his normal living behavior.

Footnotes for Chapter 2:

[2]Op. cit.

CHAPTER III

SUMMARY

In a message to new and prospective Jewish parents, The Chicago Board of Jewish Rabbis brought this to our attention:

No one in modern times questions the desirability of circumcision. What was a Jewish religious rite for thousands of years has now become standard hygienic practice for all newly-born males. This very fact, a tribute and a compliment on the part of the non-Jewish world to our tradition, contains a threat to the religious aspect of circumcision.In regard to the responses as to who or what had the most influence upon having their son circumcised, there is a tremendous difference between the Orthodox and the other three factions. This difference clearly indicates the varied approaches toward religion.

The Orthodox reasoning for performance of the ritual circumcision was Halacha, G-d's law, Torah law, and Biblical requirement. This shows that their entire view of religion is based on Torah law, and their practice of the rite of ritual circumcision is only part of 613 mitzvoth of the Torah.

The closest the Unaffiliated came to the Orthodox was in their using the word "tradition". Tradition, though, does not connotate religious practice; it might be called heritage. Actually, Tradition in itself only means a custom.

But a custom need not be necessarily religious. We find many individuals having customs which are not considered religious. If people are motivated by a religious tradition, then what kept the Unaffiliated from expressing theselves in that way? Tradition is independent of religion; custom is independent of ritual. The actual motivation involved is "peoplehood" which is not true ritual or religious.

The Reform impressed me with their answers, which were more direct and intellectual. They viewed the ritual as an enhancement to Reform Judaism, Jewish identity. However, they too felt it unnecessary to have a ritual; yet, I sense from the Reform, a more conscious and directive reason for their performance of a ritual circumcision.

Conservative are lowest on the rung. Most felt that ritual circumcision is for Jewish peoplehood, Jewish law, coupled with health benefits. The Conservative, more than the Reform and the Unaffiliates, are skating on thin ice, when it comes to a ritual circumcision. I wonder if this is not the over-all picture of Conservative Judaism.

The Orthodox are firm in their religious practice, based on Halacha; the Reform are based on Reform Judaism; the Conservative on neither G-d's law nor Reform tenets. Hence, the Conservative response is basically one of confusion and inconsistency.

Naming a baby boy is quite important to the average parent. There is a distinction between the baby having a Hebrew name and the baby perpetuating a Hebrew name. By this I mean that parents seem to have no emotional concern for the child's Hebrew name as such, being used only at Hebrew School. Nevertheless, at the ritual circumcision the naming of the child is quite relevant, for the name perpetuates after someone in the family. There is a concern that the name should be similar to the deceased -- especially if the name is transposed from a female to a male whence it has to be done with precision accuracy, so that the name should sound like or begin with the same letter as in the name of the deceased. Name-giving plays such an important role in the lives of the parents that many Temples have instituted name-giving ceremonies after their services.

Although I have stated before that the only place that a Jewish male child is given his Jewish name is at the circumcision. Nevertheless, some clergymen bend to the pressures of their inconsistent congregants. For in reality, why a ritual if we are not fulfilling a ritual?

Seeing that people are motivated by some kind of religious behavior, I wonder if it is not time that our religious leaders take a firmer hold of their role as religious leaders. Rabbis must capture the spark of religious behavioral tendency. The prerequisite for the Rabbinate, is that the Rabbi be a teacher, a "veg viser."

The Hebrew for law is Halachah, which really means "to walk the path of life," and it is the Rabbi's responsibility to be the "way-guide" on this road. If there is, on the path of some, a motivation toward the religious aspect, the Rabbi must captivate the dormant religious and spiritual feeling, and bring it out, developing it into committed religious practice.

Although, some define religion on an ethical basis, like being good, admitting no observance of the Sabbath or dietary laws; yet the fact remians that they preferred a ritual circumcision performed on their son.

At the moment, I am not so concerned about that which motivated them to have the ritual, whether or not they thought circumcision was medically recommended. The fact remains that they did use a Mohel. Using an old cliche "actions speak louder than words," they profess to an ethical religion, but they act towards the ritual.

In terms of ritual behavior, I am presently not in the position to analyze a definite distinction between religious practice and ritual practice. One might observe that ceremony is involved with ritual, and ceremony might hit a weak spot, a vulnerability in the sensual. There is a sense of nostalgia to age-old Jewish identity. It is not as cut and dry, or directed as religious practice might be.

Thus I return to the point that ritual circumcision is not merely a ritual, but it is truly a ritual practice; it is involvement. The majority of the parents were aware of what took place at the circumcision, that their son was being subjected to the knife. Yet, they called a Mohel.

As mentioned before, it seems that the first preference would have been, not the Mohel alone, but a Mohel and a physician together. Seventy-seven of all denominational tabulation preferred a Mohel. Yet sixty-eight preferred, if they had the choice, anything else than a Mohel alone. Yet, they took the Mohel!

What stopped them from taking anyone else than the Mohel alone? It could have been their confidence in the Mohel, or the Mohel's reputation, or the fact that the Mohel is on the staff of most medical hospitals. Or, it might be a combination of confidence in the Mohel, and ritual, religious feelings, along with the underlying factor of medical acceptance. Continuing, many rituals are performed at home, being deprived of the psychological sterile environment of the hospital atmosphere; a greater reason for not taking the Mohel.

The questionnaire proved that the majority of all factions are prone towards an ethical type religion: being good and kind, etc. Therefore, I suspect, from twenty plus years experience as a Rabbi and Mohel, the type of ceremony that is performed at the ritual is of great importance. The Mohel must perform a meaningful explanatory ceremony. It must not be a robot type of performance, i.e., taking out the Rabbinical guide manual. It must be personally meaningful, involving all those that are sharing with the parents the circumcision ceremony -- biblical, traditional, and contemporary explanations for the purpose of the Brith Milah, must be given. The Mohel must himself be imbued with his revered mission of inducting the eight-day old little male, as a new member of our eternal faith. We must show commitment and sincerity. Only thorugh such behaviour can we bring out the inherent but dormant religious spark that exists in every individual, and in our particular case, manifests or reveals itself through the parents' commitment to ritual circumcision.

On September 17, 1963, a letter was sent to University Hospitals by the president of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Women, Ohio branch of the national chapter. This letter was directed to the director of University Hospitals, opposing the then policy of the hospital (this policy has been changed, and the Mohel is now permitted). They opposed the policy of the Hospital allowing the doctor to circumcise with a Rabbi present. The letter indicated that the Jewish law does not acknowedge a Rabbi's recitation of prayers while the doctor performs. Thie method, they say is strictly operation, not a ritual.

How pathetic it is that a Rabbi would permit himself to destroy the beauty of the religious spark which exists in every one of us, by permitting himself to officiate at a circumcision performed upon a child prior to the eighth day, and performed by a non-observant physician (as stated in the preface).

What respect can the average individual have for Temple service, Temple commitment, if the Rabbi caters to the inconsistent religious whim of his congregants. In reality, the Rabbi is unfortunately, adhering to the ethical feeling of this congregants, and ministering to their ethical desires. Ritual circumcision is biblical; eighth-day is biblical.

What type of ceremony is this clergy man performing before the eighth day? A ritual it is not, for a ritual is the eighth day. Then what I see him doing is permitting his congregant to perform upon their baby boy, a medical function, with little smitherings of prayers, to soothe the conscience of the parent.

If time will tell that routine circumcision can no longer be tolerated by the medical profession, then it will be proven that these Rabbis were merely an accessory to the abolition of the ritual circumcision. If their presence is requested at a circumcision, this should alarm them to the realism of this religious spark spoken about. Again, they should capitalize and encourage, so that this religion feeling will blossom, not only to the fulfillment of the ritual circumcision in proper dimension, but in all areas of all religious practice.

My recent study questionnaire proved to me that people are not inconsistent out of desire; but, rather out of religious educational ignorance. The Rabbi must start teaching, he must play his role of one who must teach religious practice, rather than humanistic ethics. For, as stated before, ritual circumcision is biblical; eighth-day is biblical.

Unfortunately, as in all religious circles, there are some clergy who step away from ritual law, sometimes for monetary reasons, or various pressures prevailing on him. I cannot understand how a Rabbi or a leader of a religion performs a function in a ritual surrounding when there really is no foundation for this type of ritual. I feel that the clergy are quite responsible for this terrible inconsistency. I lay the blame upon my clergy colleagues who are failing to lead, rather than to be led.

Greater Cleveland Rabbis of all three Jewish factions, Orthodox, Conservative, and Reformed, have issued a joint statement for strengtheing the observance of the use of circumcision as the rite of initiation of a male child into the Covenant of Abraham. The eighth day was stressed. Use of a Mohel was emphasized. The fear of the increasing secularization of the practice was articulated.

Greater Cleveland rabbis of all three Jewish traditions -- reform, orthodox, and conservative -- have issued a joint statement calling for strengthening the observance of the use of circumcision as the rite of initiation of a male child into the Covenant of Abraham. The statement, issued this week, commented on the growing secularization of the practice. The statement said there was increasing use of surgeons "rather than the traditional Mohel, disregard of the Biblical command to circumcise on the eighth day (after birth) and a tendency to name a male child in the synagogue" instead of at the time of circumcision. The resolution, as adopted by the rabbis, emphasizes the essentially religious nature to Jews of the rite. The rabbis have agreed upon a campaign to bring to Greater Cleveland's Jewish community "a proper understanding of this basic Jewish rite," and to promote its non-surgical implications. They emphasized the medical benefits that they said accompany the rite. The Rabbis have urged the adoption of the following points:Yet, what good are all these articles if the Rabbi himself does not stand firm behind his words with commitment to Jewish tradition, the Jewish Torah, and the Jewish way of life? Why does the Rabbi allow himself to be manipulated into being led, instead of effectively leading others with steadfast sincerity?Use of a certified Mohel. Observance of the eighth day after birth as the proper time for the rite. Increased awareness of the rite as an expression of the "Covenantal relationship between the Almighty and His people."[1]

Footnotes for Chapter 3:

APPENDIX A

INSTRUCTIONS: HUSBAND AND WIFE, PLEASE USE SAME QUESTIONNAIRE.

HUSBAND INDICATE ANSWER BY X AND WIFE BY V.

Father's Hebrew Name _____________________

Mother's Hebrew Name _____________________

1. Do you belong to a synagogue? Yes______ No_____

Orthodox_____ Conservative_____ Reformed_____ Other _____

2. Are you intermarried? Yes______ No_____

3. If Yes, did this have an effect to influence you to have your son

ritually circumcized? Yes______ No_____

4. What is your educational Hebrew background? _______________

5. Do you want your son to attend Hebrew School? Yes______ No_____

Until Bar Mitzvah_____

Until end of Hebrew High School Graduation_____

Other_____

6. Do you know what the word Brith Milah means? Yes______ No_____

7. Do you feel your background influenced your decision to have a

Brith? Yes______ No_____

8. Did you choose the Mohel with confidence_____ Fear_____ Other_____

9. Who referred you to the Mohel?_____________________

10. Do you name a baby boy at Circumcision_____ or at Temple_____?

11. Did it make a difference to you where? Yes______ No_____

12. Who influenced this decision?______________________

13. What influenced you to have your son ritually circumcised?

__________________________________________________________

14. Who had the most influence regarding the decision?

Self_____ Grandparents_____ Rabbi_____ Friends_____

15. Did anyone discourage you to have a ritual? Yes______ No_____

If Yes, Doctor_____ Obstetrician_____ Pediatrician_____

RN_____ Practical Nurse_____ Friends_____ Parents______

Family_____ Rabbi_____ Other_____

16. Educational background in Sunday School_____

Synagogue Hebrew School_____ 2 day_____ 4 day_____

Community Hebrew School_____ 2 day_____ 4 day_____

Parochial_____ Other_____ None_____

17. Do you know the meaning of circumcision?_____

Covenant_____ Health_____

18. What do you think was done to your son?

Skin removed_____ Skin pushed back_____ Ritual_____

19. Why do you feel it was necessary to have him ritually

circumcised? ____________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

20. What was your emotional reaction to your son's circumcision?

__________________________________________________________

21. Did Mother take part? Yes______ No_____

22. Did you regret having the ritual? Yes______ No_____

Remarks __________________________________________________

23. Were you happy you had a ritual? Yes______ No_____

24. Has the ritual influenced your future plans in the religious

education for your son? Pidyan Haban_____ Bar Mitzvah_____

25. Were you afraid of having your son circumcised?

Yes______ No_____ Other Feelings__________________________

26. Were you worried about any after effects? Psychological_____

Infection_____ Bleeding_____ Other_____

27. Does the fact that your child was ritually circumcised make any

difference to you? Yes______ No_____

28. Were you ritually circumcised? Yes______ No_____

29. If negative, did you ever feel that you would have wanted a

ritual? Yes______ No_____ No Opinion_____

30. What did you envision taking place at a ritual circumcision?

____________________________________________________________

31. Is it because of the child's Hebrew name you decided to have a

ritual? Yes______ No_____

32. Do you consider yourself religious? Yes______ No_____

33. Do you observe the Sabbath? Yes______ No_____

34. What is being religious? _____________________________________

____________________________________________________________

35. Do you observe dietary laws? Yes______ No_____

Home_____ Home and Outside_____ Other_____

36. List in first priority: Sabbath_____ Dietary Law_____

Circumcision_____

37. Were you married by a Rabbi_____ or Justice of Peace?_____

38. Did you know your Hebrew names before the circumcision?

Yes______ No_____

39. Do you know it now? Yes______ No_____

40. Do you want proof in form of certificate of Ritual?

Yes______ No_____ Other_____

41. Do you know your son's Hebrew name without looking at

certificate? Yes______ No_____

42. How did you feel after the second son's circumcision?

____________________________________________________________

43. Can you compare any emotion that was different from first

experience? Less Tension_____ More Tension_____

44. Did you allow other children to remain for ceremony?

Yes______ No_____

45. Did any member of family leave during circumcision or ceremony

out of fear? Yes______ No_____

46. Did this have any effect on you? Yes______ No_____

47. Do you know the historical background for the Brith?

Yes______ No_____

48. Is it biblical or rabbinical? ________________________

49. What is meant by biblical? G-d inspired_____ G-d revealed_____

Man inspired_____

50. Did you know the meaning of Brith before the circumcision or

after?_________

51. Do you approve of your son having a Hebrew sounding name?

Yes______ No_____

52. Would you rather he had an English name? Yes______ No_____

53. Do you know what day the Brith should be performed?

Yes______ No_____

54. Are you in agreement with a pre-eighth day circumcision ceremony?

Yes______ No_____

55. Who would you prefer to circumcise your son? Mohel_____

Physician_____ Mohel with Physician in attendance_____

Physician with Rabbi in attendance_____

56. Could you state briefly why? _________________________________

____________________________________________________________

57. Did any of the above parties influence your decision?

Yes______ No_____

58. What is the Biblical history of Brith?

____________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

59. What Patriarch is connected with Brith?

Moses_____ Isaac_____ Jacob_____ Abraham_____

60. Hebrew name given because of:

Tradition_____ Perpetuate memory of deceased_____

Jewish identity_____

61. Was there complete agreement between husband and wife to have son

ritually circumcised? Yes______ No_____

Father preferred_____ Mother preferred_____

Father against_______ Mother against_______

62. Do you feel having a homeland Israel had any bearing on your

decision to have a ritual for your son? Yes______ No_____

63. Is tradition important to you? Yes______ No_____

64. Do you belong to your Temple because: Social reasons_____

Live closer_____ Commitment to Temple Idealogy_____

65. Do you enjoy_____ or find meaning_____ in the Temple Service?

66. Did you attend a Brith ceremony before you had your son

circumcised? Yes______ No_____

67. Did this influence you to have a bris? Yes______ No_____

ANY OTHER COMMENTS WELCOME: ______________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

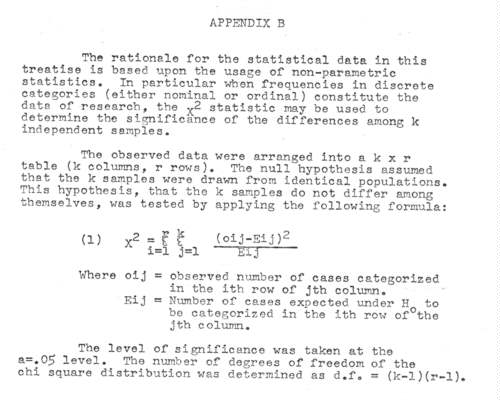

APPENDIX B

Bach-Yera-Deya, 364.

Cleveland Jewish Review and Observer, April 17, 1964, p. 1.

Exodus, 34.27.

Genesis, 17.9-14; 17.5.

JAMA, Vol. 1-213, September 14, 1970, p. 11.

Jeremiah 33.25.

Mishna-Herbert Danby, 451-13.

Mishna-Nedarim, 3-11.

Ose Shalom, 364.